Fresh Truffles

In Greece, the truffle has been known as "Ydnon" since antiquity. It was highly sought after due to its pharmaceutical and aphrodisiac properties, as well as its delicious flavour and aroma. It's no surprise that it inspired so many ancient poets and writers. Truffles were referred to as "children of the gods" by Porphyry, while Pliny regarded them as "natural marvels." Truffle has been used in culinary applications in Mediterranean countries since ancient Greece. The tubers used are called melanosporum, which is derived from the Greek words "melani" (black) and "sporum" (seed).

The truffle is not just a food, flavoring, or aroma. The truffle is a combination of all of these elements. Nothing compares to the sensation you get when you take your first bite: a delicious pleasure that awakens the senses, a state of intoxication that you wish would never end. The truffle stimulates our fifth 'taste', umami, which our tongue possesses specifically for the purpose of appreciating culinary marvels like the truffle. The first traces of truffles appeared thousands of years ago, sometime between the Babylonian culture (3000 B.C.) and the ancient Egyptians, and then reappear in ancient Greece and the Roman Empire: but that ancient object of desire was not any of the black and white truffles. (Tuber magnatum e T. melanosporum), that we know today, but ‘common’ hypogeous mushrooms, terfez or sand truffles (Choiromyces meandriformis).

Aristotle (6th century B.C.) had already spread the word that truffles had a positive effect on man's amorous abilities, so they became a 'fruit' dedicated to Aphrodite, the Roman goddess of love. The Romans saw it as an aphrodisiac, a "filter through which to have their way with women." Meanwhile, scientific interest started growing. The Greek botanist Theophrastes was the first to describe the botanical nature of the truffle as an "organism devoid of roots, originating from autumn rains accompanied by bolts of lightning sent by Jupiter." The mystery of how truffles are born will continue for centuries.

After a long period of medieval truffle silence, during which the truffle fell victim to its own aphrodisiac reputation and was thus deemed unsuitable for everyday monastic life, Italy and France finally discovered authentic, prized back and white truffles with the arrival of the refined and cultured Renaissance era. Catherine de Medici, wife of Henri II of France, served them as a star ingredient at her legendary feasts in Florence and Paris. The prized black truffle was a favorite of France's kings beginning with the Sun King Louis XIV. The playwright Molière was so fond of them that he dedicated a well-known play to them: Tartuffe.

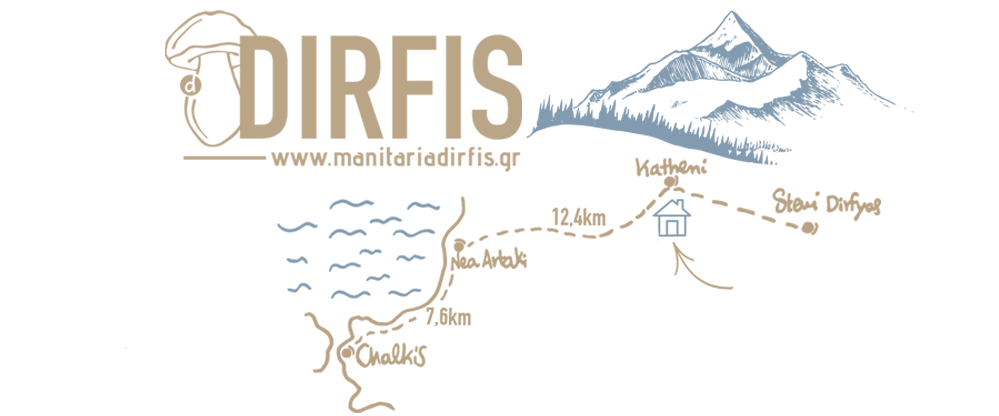

Our Wild growing Greek truffles are packed and send max 2 days after harvesting. We can send worldwide by DHL.